Abstract

Purpose

The implementation of interdisciplinary teams in the intensive care unit (ICU) has focused attention on leadership behavior. Daily interdisciplinary rounds (IDRs) in ICUs integrate leadership behavior and interdisciplinary teamwork. The purpose of this intervention study was to measure the effect of leadership training on the quality of IDRs in the ICU.

Methods

A nonrandomized intervention study was conducted in four ICUs for adults. The intervention was a 1-day training session in a simulation environment and workplace-based feedback sessions. Measurement included 28 videotaped IDRs (total, 297 patient presentations) that were assessed with 10 essential quality indicators of the validated IDR Assessment Scale. Participants were 19 intensivists who previously had no formal training in leading IDRs. They were subdivided by cluster sampling into a control group (ten experienced intensivists) and intervention group (nine intensive care fellows). Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare results between control and intervention groups.

Results

Baseline measurements of control and intervention groups revealed two indicators that differed significantly. The frequency of yes ratings for the intervention group significantly increased for seven of the ten indicators from before to after intervention. The frequency of yes ratings after training was significantly greater in the intervention than control groups for eight of the ten essential quality indicators.

Conclusions

The leadership training improved the quality of the IDRs performed in the ICUs. This may improve quality and safety of patient care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The implementation of interdisciplinary teams in the intensive care unit (ICU) to provide patient-centered care, in contrast with traditional discipline-centered care, has focused attention on the relevance of leadership behavior [1, 2]. Although leadership is conceptualized in various ways, studies emphasize the importance of leadership in the hospital and ICU for effective, coordinated, and safe patient care and safety improvement efforts [3–7]. Safe patient care is associated with a decrease in adverse events, especially when clinician leaders encourage all team members to contribute to the decision-making process for patient care [4]. Leadership behavior is defined as “the process of influencing others to understand and agree about what needs to be done and how to do it, and facilitating individual and collective efforts to accomplish shared objectives” [8].

Recent studies in a simulated environment showed that leadership behavior can be trained, and this improves subsequent team performance during resuscitation [9]. Therefore, leadership behavior is an observable, learnable set of practices—a competency, more than a trait [10]. However, without training, leadership behavior may be influenced by sex and personality [11, 12].

We conducted a study that focused on behavior of intensivists while leading interdisciplinary rounds (IDRs) in the ICU. An IDR is a patient-centered communication session to integrate care delivered by specialists from different disciplines [13–15]. Well-performed IDRs are recommended in the ICU because ineffective interdisciplinary communication among medical teams may cause preventable patient harm and severe conflicts within ICUs [15–17]. However, performing IDRs may be complicated by factors such as limited time, multiple targets, patient instability, highly technical therapies, and varied responsibilities of different providers. Therefore, leadership behavior of intensivists is important for the success of IDRs [2, 6, 18, 19].

We used the ten essential quality indicators of the validated IDR Assessment Scale to provide a coherent program to structure the content and assessment of leadership training [13, 20]. This scale had been developed to assess the quality of IDRs in the ICUs. The principal aim of this study was to critically assess the effect of leadership training on the quality of IDRs in the ICU.

Materials and methods

Study design

This nonrandomized intervention study was performed in four ICUs for adults at the University Medical Center in Groningen, the Netherlands. These ICUs (thoracic, medical, surgical, and neurologic) together admitted approximately 3,000 patients per year. There were 23 experienced intensivists, 10 ICU fellows, a varied number of junior physicians, and 288 ICU nurses employed. During typical practice, daily IDRs were organized separate from morning rounds or reports at changes of shifts as endorsed by the Society of Critical Care Medicine [15]. In a typical IDR, a discussion away from the bedside, the care plans of 12 patients were discussed (total, 120 min). The IDRs were directed by intensivists; junior physicians gave clinical patient presentations, and bedside nurses and consultants gave additional relevant and current information. The presence of specialist consultants varied with each patient and included surgeons, neurologists, and specialists in infectious diseases. The plan of care was determined by the leading intensivist and was agreed, understood, and executed by all involved providers in the ICU.

Data were collected from July 2009 to May 2011. During this period, 28 IDRs were videotaped and the participants of IDRs were informed by ward and staff meetings. Before the IDR started, the video camera was placed in the corner of the meeting room to enable rating of all participants. At the end of the IDR, the video camera was removed.

The Medical Ethical Testing Committee of the University of Groningen waived Institutional Research Board approval for videotaping IDRs in the ICUs because of the observational character of our study and because staff members were the study subjects (not patients).

Participants

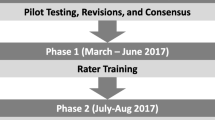

The intensivists who participated were previously untrained in leading IDRs and they were selected by cluster sampling into control and intervention groups (Fig. 1). The control group included ten experienced intensivists (nine men and one woman) from the ICUs with 3–20 years of clinical experience after graduation from training as intensivists. They participated voluntarily in being videotaped while each led one IDR and their performance was individually discussed in reference to the IDR Assessment Scale. None of the intensivists in the control group participated in the leadership training course.

The intervention group included nine ICU fellow trainees (three men and six women), and one other fellow was not included because of reallocation to another hospital. These fellows had 4–6 years of previous graduate medical experience in internal and pulmonary medicine, anesthesiology, or surgery. All fellows were experienced in leading IDRs (average, 30 IDRs each). They participated in the study because this was required for their educational program [20] and informed consent was assumed. The fellows were videotaped while leading one IDR and their performance was individually discussed in reference to the IDR Assessment Scale.

Anonymity of the participants was assured. No demographic information was collected.

Assessment of leadership

To support and assess leading IDRs, the ten essential quality indicators derived from the IDR Assessment Scale were used [13]. Development was based on literature review and Delphi rounds, and the scale was statistically tested and applied to 98 patient discussions performed in three ICUs in two hospitals. The ten extracted essential indicators were used as a checklist.

To confirm that these indicators corresponded to an appropriate assessment of leadership behavior of the leading intensivists during IDRs, we compared the indicators with a literature search about leadership in the ICU. In addition, the indicators were checked by asking critical care physicians, nurses, and trainers where it was necessary to reduce ambiguity. In both situations, no additional indicators were considered useful to guide and assess leading IDRs.

The checklist included two domains: (1) patient plan of care and (2) process. The patient plan of care domain included five essential quality indicators and reflected the technical performance from the initial identification of a patient-related goal to the evaluative phase. The process domain, which also included five essential quality indicators, reflected the ICU processes that were important to ensure that the appropriate plan of care was agreed to, understood, and performed as planned by all involved caregivers (Table 1).

All quality indicators were described in terms of observable behavior that was explained in a manual necessary for using this assessment instrument (Table 1). Trained raters qualified their observations with the definition of the quality indicator using a 3-point scale, indicating whether the behavior occurred during each individual patient presentation: (1) “no” (the behavior was not observed); (2) “doubt/inconsistent” (verbalizations or behaviors were inconsistent with the quality indicator); or (3) “yes” (the behavior was clearly observed and consistent with the quality indicator). Some items had an option “not applicable” when the indicator could not be rated. In an optimal IDR, the ten essential quality indicators were rated with “yes” or “not applicable” [13].

Training of raters to assess patient discussions

The first three raters included one intensivist, one ICU nurse, and one author (E.T.H.). They were trained by assessing nine videotaped patient discussions led by different intensivists of the control group. Responses were evaluated by the manual to confirm that definitions were applied uniformly and by testing the interrater reliability. When the interrater reliability was at least 0.70, their training was considered effective and they were allowed to rate 90 other patient discussions. Owing to the large number of patient discussions of the before and after tests, another three raters were trained and tested with the same procedure. The quality of the individually tested patient discussions was checked by random testing of patient discussions by another rater and testing if interrater reliability was at least 0.70.

Raters were not informed about the details of the intervention.

Intervention

The intervention (IDR leadership training program) included three sessions: (1) preparation; (2) a 1-day training; and (3) feedback. The preparation session focused on leading IDRs in typical practice and included a videotaped and analyzed IDR led by each participant (Fig. 1).

The 1-day training session was performed in a simulated and videotaped environment. Videotaping team performance in well-controlled study settings allowed rigorous assessment of complex interactions during realistic IDR situations without putting patients at risk [9]. The training was consistent with principles of adult learning and behavioral modeling, and it incorporated the following elements: multiple learning activities; small group skill practice and problem-solving sessions; performance feedback and reinforcement of newly learned skills; and a planning assignment for on-the job applications [20–22]. These elements were processed into four real-life, progressively complex IDR scenarios about patient plan of care and conflicting situations. The fellows participated in these scenarios as leading intensivists, and the roles of other IDR team members (ICU nurses, junior physicians, and specialist consultants) were performed by ICU care professionals who had experience in performing roles in simulation courses. Each scenario was evaluated with the participants in reference to the ten essential quality indicators by two trainers in communication skills who were familiar with daily ICU practice.

The feedback session of the intervention group was performed as part of the regular practice in the ICU at approximately 6 weeks after the 1-day training session and was based on a new videotaped and analyzed IDR that had been led by each trained participant. This also was individually discussed in reference to the IDR Assessment Scale.

Data analysis

Confirmative factor analysis of the 10 essential quality indicators was performed with 98 patient discussions [23, 27].

Internal consistency of the checklist with the 10 essential quality indicators was measured for 198 videotaped patient presentations with Cronbach α.

Interrater reliability was tested by three raters who examined the indicators in nine randomly selected patient discussions of the control group. A multirater Cohen kappa calculator was used to assess outcomes per quality indicator for the three raters of each patient discussion [24]. Adequate interrater reliability was defined by κ ≥ 0.70 [25, 26].

The intraclass correlation of the first nine patient discussions was examined by measuring the average score correlation between pairs of raters (one intensivist [rater 1]; one author [E.T.H., rater 2]; and one ICU nurse [rater 3]). Pearson correlation coefficients (r) were determined.

The Mann–Whitney U test for paired comparisons of each essential quality indicator was used to compare the results of the control and intervention groups about the quality of leading IDRs. In all cases, the Bonferroni adjustment was used and statistical significance was defined by P ≤ 0.03 (Electronic Supplementary Material).

Results

Confirmative factor analysis with 98 patient discussions revealed 10 essential quality indicators with factor loadings on the first domain of the IDR Assessment Scale of greater than 0.65 (Table 1).

Internal consistency was acceptable (α = 0.72).

The interrater reliability of nine patient presentations by three raters was satisfactory (κ = 0.85), and the remaining patient discussions of the control group were further tested by these raters separately. To diminish bias from shared understanding from the developed methods, another 20 patient presentations were corroborated by an additional independent nonmedical rater which also showed adequate agreement (κ = 0.82). This procedure was repeated with three additional raters (κ = 0.75).

Intraclass correlation coefficient (0.72) showed fair reproducibility between the observers. The overall item score correlations between the first three raters were excellent. There was a significant correlation between rater 1 and rater 2 (r = 0.83; P < 0.0001); rater 1 and rater 3 (r = 0.8; P < 0.000); and between rater 2 and 3 (r = 0.94; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2).

Intraclass correlation to evaluate the correlation between different raters of the Interdisciplinary Rounds Assessment Scale scores. The average score correlation was measured between pairs of raters: rater 1, intensivist; rater 2, first author; and rater 3, ICU nurse. The x and y axes represent average rater scores on all 19 quality indicators. a Score correlations between rater 1 and rater 2 (r = 0.83; P < 0.0001). b Score correlations between rater 1 and rater 3 (r = 0.8; P < 0.000). c Score correlations between rater 2 and rater 3 (r = 0.94; P < 0.0001)

The Mann–Whiney U test was applied to 28 IDRs and included 297 videotaped patient presentations subdivided in three groups: (1) control group (99 presentations); (2) intervention group (99 presentations, test before training); and (3) intervention group (99 presentations, test after training) (Fig. 1).

Comparison of results for the control group and the intervention group before training showed that the frequency of “yes” ratings was significantly greater in two of the ten essential indicators for the control group (Table 2).

Comparison of the intervention group before and after training showed that the frequency of “yes” ratings was significantly increased after training for seven of the ten essential quality indicators (Table 2).

Comparison of results for the control group and the intervention group after training showed that the frequency of “yes” ratings was significantly greater in eight of the ten quality indicators for the intervention group (Table 2).

Discussion

The present intervention study showed that a leadership training program for IDRs improved seven of the ten essential quality indicators of the IDR Assessment Scale from before to after training, and the intervention group after training had better performance than the control group in eight indicators. The study was accomplished with minimum load for daily work in the ICU organization because of the use of a simulation environment for training and the real-life setting of the preparation and completion sessions. Furthermore, the sustained effect of the intervention, measured at 6 weeks after the training, suggested that the training effect persisted and that training could be applied to clinical practice.

Despite the importance of leadership, leadership training is limited in the curricula of most medical schools, which emphasize molecular, cellular, and organ-system dimensions of health and disease [21, 28, 29]. Literature review identified only one cohort study about leadership in the ICU environment that measured leadership skills of intensivists [7] and one intervention study about collaborative communication of nurse and physician leadership in the ICU with positive side effects on leadership skills [22].

The present study showed that leadership, focussed on leading IDRs, can be reliably trained in a simulated environment. A strength of this study was the use of videotape, which identified issues that may not have been obvious immediately for intensivists [9]. Reviewing videotaped sessions may be more effective in providing feedback and detecting consequences for other team members and the patient’s plan of care.

Limitations of the present study included those inherent with a single-center intervention study, such as a limited potential to generalize results. A second limitation concerned the design of the study; the study would have been better balanced if the participants had been allocated randomly to control or intervention groups, and there was no measurement of the control group while they had the list of the ten indicators. These design issues were necessary for study feasibility. Scenario training in a simulation setting is common in resuscitation education or crew resource management training, but uncommon in learning to lead IDRs.

Another study limitation concerned the level of clinical experience of the two groups, which differed substantially at the beginning of the study. Intensivists of the control group were more experienced but had been trained primarily with the traditional “see one, do one, and teach one” approach. The participants of the intervention group had fewer years of professional experience as intensivists, but they were more frequently trained by modern training systems, which may have improved the positive results of the leadership training. The improvement also may have occurred, in part, because of their intensive care medicine education which was continuing during the 6 weeks of the study. In addition, the intervention was multifaceted because the preparation and completion sessions were held in the ICU environment but the training was done in a simulated environment; this may have limited the ability to determine which components of training were most important. In personal communication with the first author, the fellows stated that detailed feedback was valuable with a checklist after the videotaped IDR in regular practice and during the training. Before this training, feedback was more random because of a lack of indicators. Furthermore, although the participants had been asked to ignore the videotaping of the sessions, the awareness of being videotaped may have affected the discourse in the study IDRs.

The clinical relevance of a coherent training program to lead an IDR concerns the relation between team leadership and team performance, as suggested previously [5]. Acute care medical teams have a hierarchical structure, and the behavior of intensivists may markedly influence the perception and behavior of other team members.

Improving leadership by training the intensivists may be a useful and less costly intervention to influence team members than training the entire ICU team. This also was confirmed by a recent update about interprofessional education which revealed low evidence that organized team training will improve team performance [30]. Although women doctors may demonstrate less leadership behavior without training [11], all untrained clinicians, regardless of level of experience or sex, may benefit from a leadership course to improve quality and safety of care.

The leadership training course, guided by the ten essential indicators of the IDR Assessment Scale, was derived from daily practice and hence easily applicable for the raters. The high scores in interrater reliability and intraclass correlation between the raters show that the assessment scoring scale is indeed independent of the professional background of the individual raters.

Further study may include the application of this training program, based on the essential quality indicators as a checklist, to other ICUs or departments in health care, and it may be necessary to modify the training to further test its general applicability. In addition, it may be helpful to investigate whether feedback for indicators of leading behavior during rounds may generate similar positive results for the control group as noted with the intervention group. It also may be helpful to expand the effect of training leadership skills on the predictive value for outcomes such as staff satisfaction, patient and family satisfaction, or clinical outcomes.

In conclusion, the present study showed that the quality of leadership may be reliably trained and measured for IDRs in ICUs. Leadership behavior may be effectively trained in a simulation environment, with real-life IDR scenarios including conflicting situations and workplace-based feedback in the preparation and feedback phases. This study provides a basis for further work on training leadership in ICUs and determining the effect of leadership training on improving the quality and safety of patient care.

References

Curtis JR, Cook DJ, Wall RJ, Angus DC, Bion J, Kacmarek R, Kane-Gill SL, Kirchhoff KT, Levy M, Mitchell PH, Moreno R, Pronovost P, Puntillo K (2006) Intensive care unit quality improvement: a “how-to” guide for the interdisciplinary team. Crit Care Med 34:211–218

Ten Have EC, Tulleken JE (2013) Leadership training and quality improvement of interdisciplinary rounds in the intensive care units. Crit Care 17(Suppl 2):522. doi:10.1186/cc12460

Verma AA, Bohnen JD (2012) Bridging the leadership development gap: recommendations for medical education. Acad Med 87:549–550

Reader TW, Flin R, Mearns K, Cuthbertson BH (2009) Developing a team performance framework for the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 37:1787–1793

Reader TW, Flin R, Cuthbertson BH (2011) Team leadership in the intensive care unit: the perspective of specialists. Crit Care Med 39:1683–1691

Stockwell DC, Slonim AD, Pollack MM (2007) Physician team management affects goal achievement in the intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med 8:540–545

Manser T (2009) Teamwork and patient safety in dynamic domains of healthcare: a review of the literature. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 53:143–151

Malling B, Mortensen L, Bonderup T, Scherpbier A, Ringsted C (2009) Combining a leadership course and multi-source feedback has no effect on leadership skills of leaders in postgraduate medical education. An intervention study with a control group. BMC Med Educ 9:72

Hunziker S, Bühlmann C, Tschan F, Balestra G, Legeret C, Schumacher C, Semmer NK, Hunziker P, Marsch S (2010) Brief leadership instructions improve cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a high-fidelity simulation: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med 38:1086–1091

Swanwick T, McKimm J (2011) What is clinical leadership… and why is it important? Clin Teach 8:22–26

Hunziker S, Laschinger L, Portmann-Schwarz S, Semmer NK, Tschan F, Marsch S (2011) Perceived stress and team performance during a simulated resuscitation. Intensive Care Med 37:1473–1479

Streiff S, Tschan F, Hunziker S, Buehlmann C, Semmer NK, Hunziker P, Marsch S (2011) Leadership in medical emergencies depends on gender and personality. Simul Healthc 6:78–83

Ten Have EC, Hagedoorn M, Holman ND, Nap RE, Sanderman R, Tulleken JE (2013) Assessing the quality of interdisciplinary rounds in the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.12.007

Ten Have ECM, Nap RE (2013) Mutual agreement between providers in intensive care medicine on patient care after interdisciplinary rounds. J Intensive Care Med. doi:10.1177/0885066613486596

Kim MM, Barnato AE, Angus DC, Fleisher LA, Kahn JM (2010) The effect of multidisciplinary care teams on intensive care unit mortality. Arch Intern Med 22:369–376

Azoulay E, Timsit JF, Sprung CL et al (2009) Prevalence and factors of intensive care unit conflicts: the conflicus study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 180:853–860

Rhodes A, Moreno RP, Azoulay E et al (2012) Prospectively defined indicators to improve the safety and quality of care for critically ill patients: a report from the Task Force on Safety and Quality of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM). Intensive Care Med 38:598–605

Reader T, Flin R, Lauche K, Cuthbertson BH (2006) Non-technical skills in the intensive care unit. Br J Anaesth 96:551–559

Ellrodt G, Glasener R, Cadorette B et al (2007) Multidisciplinary rounds (MDR): an implementation system for sustained improvement in the American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines program. Crit Pathw Cardiol 6:106–116

CoBaTrICE Collaboration (2011) International standards for programmes of training in intensive care medicine in Europe. Intensive Care Med 37:385–393

CoBaTrICE Collaboration, Bion JF, Barrett H (2006) Development of core competencies for an international training programme in intensive care medicine. Intensive Care Med 32:1371–1383

Boyle DK, Kochinda C (2004) Enhancing collaborative communication of nurse and physician leadership in two intensive care units. J Nurs Adm 34:60–70

Have EC, Tulleken JE (2013) Assessing the quality of interdisciplinary rounds. Crit Care 17(Suppl 2):P521. doi:10.1186/cc12459

Randolph JJ (2008) Online kappa calculator. http://justusrandolph.net/kappa. Accessed 1 Dec 2011

Randolph JJ (2005) Free-marginal multirater kappa: an alternative to Fleiss’ fixed-marginal multirater kappa. Joensuu University Learning and Instruction Symposium 2005. ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED490661

Hawthorne G, Richardson J, Osborne R (1999) The Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL) instrument: a psychometric measure of health-related quality of life. Qual Life Res 8:209–224

Hair JF, Tatham RL, Anderson R (2005) Multivariate data analysis. Prentice-Hall, New Jersey

van Mook WN, de Grave WS, Gorter SL, Muijtjens AM, Zwaveling JH, Schuwirth LW, van der Vleuten CP (2010) Fellows’ in intensive care medicine views on professionalism and how they learn it. Intensive Care Med 36:296–303

Veronesi MC, Gunderman RB (2012) Perspective: the potential of student organizations for developing leadership: one school’s experience. Acad Med 87:226–229

Reeves S, Perrier L, Goldman J, Freeth D, Zwarenstein M (2013) Interprofessional education: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes (update). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3:CD002213

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all ICU professionals who participated in the videotaped sessions. We thank H. Delwig, intensivist of the Critical Care Department, for development of the course scenarios and H.E.P. Bosveld for performing the statistical analysis.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no commercial association or financial involvement that might pose a conflict of interest connected with this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ten Have, E.C.M., Nap, R.E. & Tulleken, J.E. Quality improvement of interdisciplinary rounds by leadership training based on essential quality indicators of the Interdisciplinary Rounds Assessment Scale. Intensive Care Med 39, 1800–1807 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-013-3002-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-013-3002-0